What Shall We Overcome?

Racism, the Imbalance of Power, and the Response of the Prophetic Voice

Comments are welcome at the end of the commentary.

NOTE: AN UPDATED REVISION OF THIS COMMENTARY CAN BE READ CLICKING 'HERE'

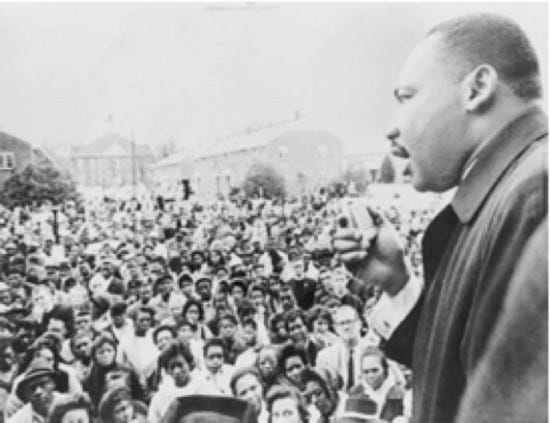

“They told us we wouldn’t get here. And there were those who said that we would get here only over their dead bodies, but all the world today knows that we are here and we are standing before the forces of power …”

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., speaking at the conclusion of the march from Selma to Montgomery, March 25, 1965

Preface

I’m writing these comments at a particular moment in time. And yet, unlike a week-old newspaper, the themes and issues have a persistently endless quality about them that just won’t seem to go away. The annual observance of Black History Month has just concluded. And in a few days, our nation’s first black president will commemorate the 50th anniversary of the landmark civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, by standing on a bridge named after a Confederate general and reputed early Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan, Edmund W. Pettus. In the last few years we have witnessed a resurgence of racial strife, as the recurrent curse of our American story. Names and phrases like Trayvon hoodies, Ferguson and “I can’t breathe” have become protest chants. Hands raised high overhead are no longer accompanied with shouts of “Hallelujah,” but rather, “Don’t shoot.” Equipping law enforcement personnel with body cams is now recommended to record whatever transpires, after the fact. And all the while, political forces work to dismantle, disempower, disenfranchise and discourage voting rights in our democratic society. One citizen, one vote, one voice is a constitutional principle that seems challenged and tested, once again. It took a half-century to elapse after those two marches from Selma, Alabama in 1965, for a docu-drama retelling that story gets an Oscar nomination. And the anthem, Glory wins Best Original Song at the Academy Awards:

One day, when the glory comes It will be ours, it will be ours Oh, one day, when the war is won We will be sure, we will be here sure Oh, glory, glory, glory.

One fine, glorious day it shall come, the singer sings; just as both the ancient prophets and the prophets of our own age once proclaimed. It understandably leaves us wondering when that day will come? But perhaps it is not so much a matter of when we shall overcome, but the ever-present what? And in the naming of the what, we might also ask where is the echo of the prophet’s voice in all of this?

Naming the What

The short answer to the question of what we hope we shall one day overcome is the endemic racism that persists in America. In civic society – as in the biblical story – there is the letter of the law, and the spirit of the law’s intention. Civil rights can be the law of the land, and still miss the mark when it comes to the heart of the matter. So the longer and more difficult answer to what we must overcome lies in a penchant for power of one human being over another that results in the kind of inequity that surpasses the simple cry for moral justice. The repeated historical reality is that such a precarious imbalance of power eventually descends into such disequilibrium that it becomes untenable and unsustainable.

We must overcome the penchant for power of one human being over another that results in the kind of inequity that surpasses the simple cry for moral justice.

It is also the same dynamic that can find expression in tribal, racial or ethnic conflicts, warring factions between nation states, gross economic disparity and the “prosperity” gap, and even radical extremism that usurps religious traditions to construct aberrant belief systems and consequent behavior. For example, in the Christian faith tradition, the authentic letters of Paul have been used to both defend and condemn slavery. There are the familiar lines in Galatians 3 about faith superseding that which had previously guided right behavior; namely, the law (of Moses). Such faith that expresses itself through “oneness in Christ” not only fulfills the law, but ameliorates all previous distinctions between gender, tribe or race, or positions of dominance or subservience. “There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female,” Paul writes, “for all of you are one in Christ Jesus.” (Gal. 3:28) But then there’s the shortest Pauline epistle, the Letter to Philemon. The traditional interpretation to the story relates how a runaway slave named Onesimus has somehow shown up in Rome, where Paul is imprisoned. Onesimus is being sent back to his owner, Philemon; who himself is a relatively well-to-do leader of an early Christian house church. So the story is about two masters swapping one slave. But the backstory and deeper meaning is about reconciliation and restoration of human relationships.

“ … that you might have him back for ever, no longer as a slave but as more than a slave, a beloved brother—especially to me but how much more to you, both in the flesh and in the Lord. … So if you consider me your partner, welcome him as you would welcome me. If he has wronged you in any way, or owes you anything, charge that to my account.” (1:16-17)

Some scholars now question whether Onesimus was actually an indentured servant to Philemon; just as Paul refers to himself as a “prisoner” not of Rome, but of Christ; with his own subjugation to the gospel. In point of fact, a runaway slave in 1st century Asia Minor would have found no refuge anywhere, nor had any future apart from his master. Those who might credit Paul with being a staunch abolitionist and a man ahead of his time might do well to remember he was still very much a part of an ancient world distinctly different than our own. David Galston, Academic Director of the Westar Institute, makes two helpful points in this regard:

“It is easy to make the historical Paul sound congenial to today's world. He resisted slavery, he promoted equality, and he had little sympathy for wealthy folk who exploited poor folk. Still, we must be careful not to make Paul too congenial by forgetting that he was still a person of the first century. His solutions to world problems were still "otherworldly" solutions. Paul consequently is an example of both the promise of Christianity (with his emphasis on equality) and the problem of Christianity (with his emphasis on apocalyptic solutions to world problems).”

The promise and problem of traditional Christianity are not dissimilar to the promised ideals of our democratic society that falls short awaiting it’s own fulfillment. Fifty years ago the hymn of the civil rights movement was We Shall Overcome (someday).

“Paul is an example of both the promise of Christianity (with his emphasis on equality) and the problem of Christianity (with his emphasis on apocalyptic solutions to world problems).”

The Problem of When

People get ready, there's a train a-comin' You don't need no baggage, you just get on board All you need is faith to hear the diesels hummin' Don't need no ticket, you just thank the Lord.

Singer/songwriter, Curtis Mayfield, 1965

A predominant theme in traditional Black spirituals is the hope things will be better in a next life. And that hope somehow makes suffering through the adversities of this life more bearable. Think of the many traditional folk tunes, such as Swing Low, Sweet Chariot (“comin’ for to carry me home”), or even more contemporary songs like People Get Ready, a song written by Curtis Mayfield and originally released by The Impressions the very same year as the Selma march. The biblical story of exodus and deliverance from bondage to freedom in a promised land is a promise yet to be fully realized; except by “faith,” according to Paul. Likewise, there’s Jesus’ repeated depictions of the “reign of God” that is “at hand,” and yet to come. It can be viewed as either a continuation of that ancient, prophetic future hope; as well as a call to usher in the kingdom here and now. This dichotomy seems to be borne out, time and again. The Edmund Pettus Bridge was once a pivotal “crossing over” moment in our society. Now old men and women who once dreamt dreams and visions wonder if today’s youth will take up that same struggle all over again. In 1965, a dear friend of mine was a 30-year old Episcopal priest from Southern California and vicar of a small mission congregation. He was part of a delegation of clergy chosen to participate in the conclusion of the Selma to Montgomery march. “We went to love the hell out of Alabama,” he said. When he arrived in Montgomery he decided to first attend a church service that Thursday morning. “The massive nave of the red brick church was marked by stained glass windows,” Fred recalls. “And in one window were the words ‘He suffered and died for all people without respect to origin, race or color.’” “Here,” my friend said, “I found in stained glass my real reason for being in Montgomery. And I couldn’t help but wonder at the weakness of Christianity.” Fifty years later, he wonders how we ever could have ended up back at the same bridge that should have led us so much, much further than we’ve come. “The march goes on, and it always will,” he has resolved.

Standing up with a Strong Voice

Randy is a participant in the progressive Christian faith community I lead. He works with the developmentally disabled in a local community program. One of his clients is an African American named Dwayne, who gets around by a walker and wheelchair. He has a speech impediment, and is often difficult to understand unless one listens closely. But Dwayne is also an advocate for the disabled. Dwayne was part of a group which Randy recently took to see the film, Selma. Afterward, when asked what Martin Luther King Jr. meant to him, Dwayne said, " Standing up with a strong voice." Speaking with a strong voice is the role of a prophet. In the prophetic tradition the tongue of those who stumble in their speech is set on fire to foretell that future time when the mute might shout with joy (Is.35:5). The one who now is silenced will one day stand and speak. But the prophet is also the one who – at the risk of our displeasure – comes to expose secrets of our hearts. Who will risk life and limb once more, to speak to what we are called to overcome, once and for all? David Oyelowo, who portrayed Martin Luther King, Jr. in the film, Selma, reflected on the actor’s role, saying, “When you see Dr. King giving those speeches, you see that he is moving in his anointing. Many historians just see King as a civil rights leader, but they don’t fully understand how being a minister and a faith leader made his role in the movement possible. … I don’t think [King] could have stuck … to the theme of nonviolence and love in the face of hate if he didn’t feel that command. faith was the engine for what he believed in and how he acted.” Likewise, Cong. John Lewis, who was 18 years old when he participated in the first, disastrous march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma on March 7, 1965, has spoken of the prophet and the prophet’s call. “When you listened to Martin Luther King, Jr. you had to move …” he’s said.

William Pettus Bridge, Selma, Alabama, 1965 In his New York Times bestseller, March, Lewis relates his now familiar story how he was nearly clubbed to death by an Alabama state trooper’s nightstick. In a recent interview for the Aspen Institute, he reflected further:

“I discovered -- attending the nonviolent workshops – that if you’re going to lead, you must be a headlight and not a taillight. We studied the way of peace, the way of love, the way of nonviolence. We studied what Ghandi attempted to do in South Africa, and accomplished in India. We studied Thoreau and civil disobedience. We studied the great religions of the world. We studied What Dr. King was all about in Montgomery. And many of us in Nashville grew to accept the way of peace, the way of love, the way of nonviolence as a way of life – not simply as a technique or as a tactic.”

When asked what advice he would give to youth to address injustices they see in the world today, Cong. Lewis concluded, “Growing up … my parents and grandparents would say, don’t get in the way. But I say, find a way to get in the way. Find a way to get in trouble, good trouble, necessary trouble, and be prepared to speak up and speak out. Be bold. Be courageous. If you see something that is not right, that is not fair, that is not just – you have a moral obligation, a mission, and a mandate to get in the way and make some noise.”

Leaving Egypt together

“It is easier to get the people out of Egypt, than to get Egypt out of the people.”

Progressive Christian blogger, Chris Glaser, recently referred to Laurel Dykstra’s book, Set Them Free: The Other Side of Exodus. In the book, there is a paraphrase from the Pan African Healing Foundation which asks if people of relative privilege, like myself, are capable of change. Quoted is a wonderful old African American proverb that says, “it is easier to get the people out of Egypt, than to get Egypt out of the people.” Glaser writes,

“For people of privilege, for whom Egypt and empire have offered not only security and comfort but everything we have known, leaving Egypt and ridding ourselves of “Egyptian” ways and habits will be slow and hard. Acknowledging our role in empire is a first step in the long, slow journey out of it.”

So I think of an old bridge in Selma, Alabama. I think about the intended purpose of every bridge meant to take us to another side, another place, about exodus and deliverance. And I think again about the old story of two men with those strange names, Onesimus and Philemon. The deeper message and backstory to that tale is about a broken relationship between two men who ought to be considered “brothers.” Like racism itself, slavery was only a symptomatic example of a human domination system that always results in inequity, injustice, discord and estrangement. Paul’s appeal for reconciliation and restoration is the underlying point of the story, And Paul’s entreaty lays that moral obligation at the feet of the one who must stoop down in an act of disempowerment; in order to establish a new order and balance of power to what has been an imbalance. It is then that a curse such as the one repeatedly borne by our own history can become a blessing, when it transcends the mere enforcement of civil rights in favor of the common good of right relationships.

Paul’s entreaty lays that moral obligation at the feet of the one who must stoop down in an act of disempowerment; in order to establish a new order and balance of power to what has been an imbalance.

© 2015 by John William Bennison, Rel.D. All rights reserved.

This article should only be used or reproduced with proper credit.

To read more commentaries by John Bennison from the perspective of a Christian progressive go to