Rich Man, Poor Man: The Bigger Message of a Jesus Ethic

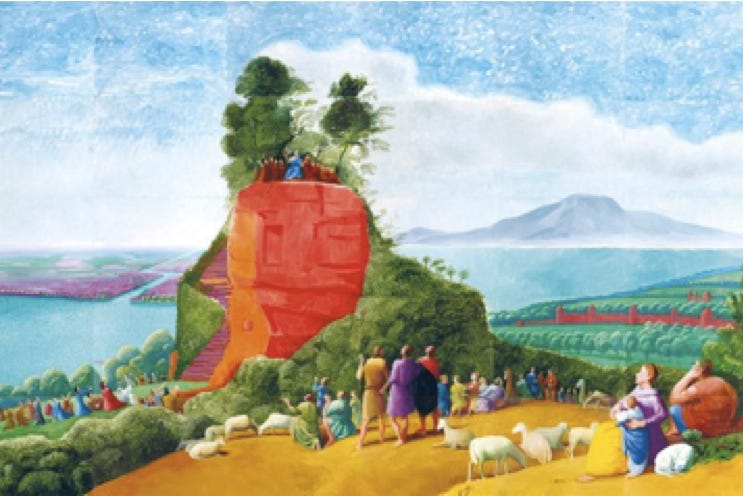

“A Bigger Message” by renowned contemporary artist, David Hockney, is a re-imagined rendering of the original Claude Lorrain’s 17th C. painting entitled, "Sermon on the Mount"

Introduction to a Series on the Teachings of a Galilean Sage: The Sermon on the Mount

"The poorest man is the one whose only wealth is money." Anonymous

Preface

A news release by Oxfam recently reported the world’s 85 richest individuals now own as much as the poorest half of the 7 billion members of the human family. Meanwhile, our U.S. President announced plans to visit the Pope on his upcoming 4-day whirlwind European trip. Speculation abounds whether they will discuss any sort of unofficial economic alliance over Francis’ unwavering message advocating on behalf of the global poor, and Obama’s expressed concern for the vanishing middle class in this country; as well as his pitch to raise the minimum wage. World leaders, politicians and pundits alike, are no longer simply calling the economic disparity a gap between those who have more, and those who have less of the world’s riches and resources. It is rather a chasm that has reached astronomical proportions. Labels like inequitable, unfair or unjust are no longer adequate to describe it. Instead, it is described in more blunt terms like untenable and dangerous. It is the stuff of which revolutions are made. In contemporary terms – and if one considers how poverty and ignorance often go hand in hand -- it is arguably gross economic disparity as much as anything else that fuels desperate acts of terrorism. It’s not an excuse, only a partial explanation. Consider how in this day and age, it is profoundly telling that security concerns have overshadowed the Olympic winter “games” in Sochi; where all the peoples of the world are about to convene to compete in what was originally supposed to be a spirit of good sportsmanship among nation states. While some will jockey to win the gold, silver and bronze, the heavily guarded venues will have to defeat those suspected “black widow” suicide bombers who think they have nothing left to lose. Amidst all this, one can revisit and explore the age-old plotline of rich man, poor man, and what might constitute for progressive Christians a Jesus ethic that might not only give us our own particular perspective; but additionally, the more challenging question of what we do about it. Biblical scholars generally consider those teachings attributed to Jesus in that part of Matthew’s gospel, commonly referred to as the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5-7, with the corollary being the Sermon on the Plain, Luke 6), as likely comprising much of what can be considered most authentically and historically the real deal. But reaching back as close as we can to who the historical Jesus may have been is not the end of it. At the heart of it, a Jesus ethic itself has little concern with what you believe about the man, but what you do about the message.

At the heart of it, a Jesus ethic itself has little concern with what you believe about the man, but what you do about the message.

For those who might consider ourselves progressive Christians, but who still find ourselves economically better off than the vast majority of the world’s people, how might we authentically and honestly engage this ethic?

Picture This

When Jesus saw the crowds, he went up the mountain; and after he sat down, his disciples came to him. Then he began to speak, and taught them, saying …Matthew 5:1-2

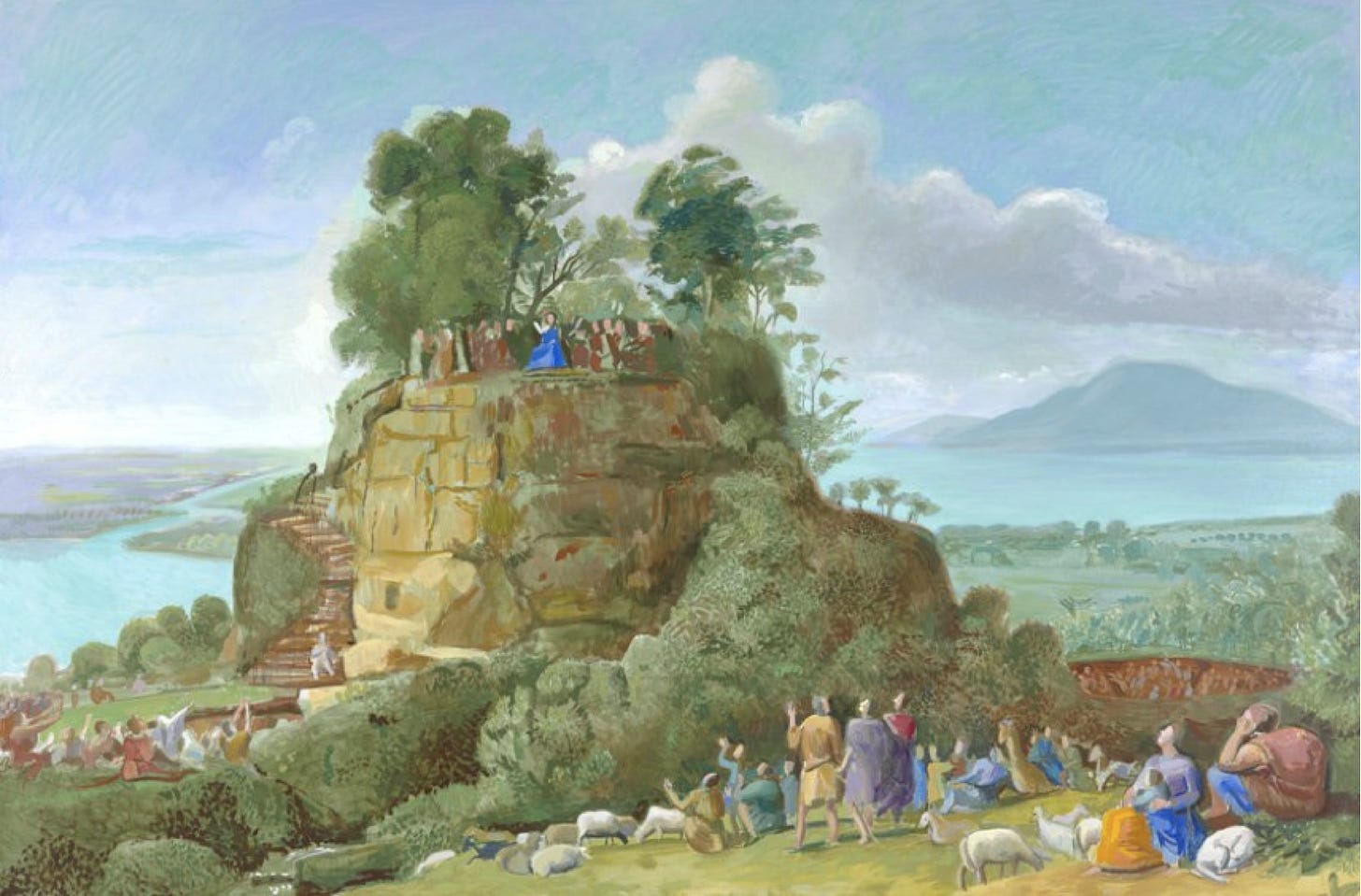

In 1656 CE, the French artist Claude Lorrain (customarily simply referred to as Claude, in English) painted “The Sermon on the Mount.” If a picture is worth a thousand words, Claude took however many words are to be found in three chapters of Matthew’s gospel, and provided us with a literally graphic interpretation of Jesus’ teachings. While Matthew simply suggests a knoll or modest promontory of some kind, from which Jesus delivered what Matthew has undoubtedly collected in a compilation of various sayings, the artist’s imagination places the figure atop what would have easily been recognized in Jesus’ day as Mt. Tabor; a monadnockrising abruptly from gently sloping or level surrounding land. Why?

Mt. Tabor, 19th C engraving In traditional symbolism, ascension to a mountaintop is the place of revelation, of course. It is the place of burning bushes that are not consumed and divine commandments carved in stone. It is the place from which one can look and see the other side, and a whole new way of seeing things. It was also the gospel setting for Jesus’ transfiguration before the eyes of his earthly companions. In fact the Franciscans eventually built the Church of the Transfiguration on Mt. Tabor as the traditional site for just such a revelation. It is therefore quite understandable that the artist would choose to perch Jesus on such a lofty place, in order to validate the significance of the message. Even the size of Claude’s painting being substantial for its day – approximately 3.5’x 8’ – commands a sense of prominence.

“Sermon on the Mount” – Claude, 17th C. The Frick Museum In the painting, Jesus’ distant figure is depicted seated among his inner circle, atop the mountain; while down below shepherds and other low-lives mill about in the foreground, as they strain their necks and cock their heads to hear his strange and welcome words of comfort and consolation:

How fortunate like the gods are those who are humble in spirit, for the [benign and salvific] governance of heaven shall be theirs;

How fortunate like the gods are those in mourning, for consolation will be theirs;

How fortunate like the gods are those who are gentle, for they will have the earth as their inheritance;

How fortunate like the gods are those who hunger and thirst for conformity to the governance of benign justice, for they shall be satisfied;

How fortunate like the gods are those who give alms to the needy, for when their time of need comes, they will be taken care of;

How fortunate like the gods are those whose hearts are free of guile, for they shall see

How fortunate like the gods are those who work for peace, for they will be known as children of God;

How fortunate like the gods are those who are persecuted because they hold out for benign justice, for to them will belong that very governance …

Mt. 5:3-10, translated by Harry Cook [Note: An excellent commentary to accompany this translation is here]

In Claude’s rendition of such a scene, you’d think Jesus must have bellowed with cupped hands in order for his words to come within earshot of the larger crowed, but no matter. If one knows the text to those so-called Beatitudes as he begins his preaching, one can easily imagine what those listening to this strange sermon might have uttered under their breath to each other. “Did you hear what he said?” “Is he talking about us? We’re the fortunate ones?” “Sounds too good to be true,” says another. And yet another, “But I hear he practices what he preaches. You don’t see that everyday. Not in the temple anyway.”

A Bigger Message

When the contemporary artist David Hockney found Claude’s work in the Frick Museum in New York it had been badly damaged from a fire. Hockney set out to restore what he found to be of interest in the piece by creating a series of six renderings of his own. In his final version, he toiled in his football field-sized studio to produce a huge version approximately 15’x40’, and consisting of 30 separate canvases joined together like a jigsaw. [See picure, page 1] Simply entitled, “A Bigger Message,” Hockney no doubt means the piece to again be taken literally. That is, it is not a suggestion he’s trying to upstage Jesus’ original words, but only Claude’s spatial expression and perspective When an interviewer once asked Hockney why he chose a religious subject, he replied, “, “Well, it wasn’t really a religious subject. A religious subject is the crucifixion or the annunciation, but this is actually just a sermon telling you how to live really, isn’t it?” If the idea of being a religious type – let alone a Christian -- is merely about such things as crucifixion and annunciation, then I would probably agree the collection of teachings found in the Sermon on the Mount certainly offers a bigger message than what any run-of-the-mill religious commodity can offer. It is, in fact, all about teaching us how we might truly live; in every sense of that term. Indeed, art imitates life.

The Sermon on the Mount certainly offers a bigger message than what any run-of-the-mill religious commodity can offer. It is, in fact, all about teaching us how we might truly live; in every sense of that term. Indeed, art imitates life.

In this regard, there is an undeniable, all-inclusive message that stands as a direct challenge in these ethical instructions with regard to those of us who would feign to live within earshot of Jesus’ words; but shirk from the kind of “benign governance” and equitable justice to which those beatitudes refer. Those who would, in fact, seek to be “fortunate like the gods” are those who upend conventional thinking and topple the power structures as they are typically framed throughout the whole of human history. Of particular note, Luke’s version of the very first beatitude is undoubtedly closer to the mark when Jesus refers to the blessed poor, and not just those who are “poor,” or “humble” “in spirit.” We should not be coy or evasive here. Poor is poor; as in working full time your whole life long with a minimum wage that still leaves one living below the poverty level (per U.S. Labor statistics).

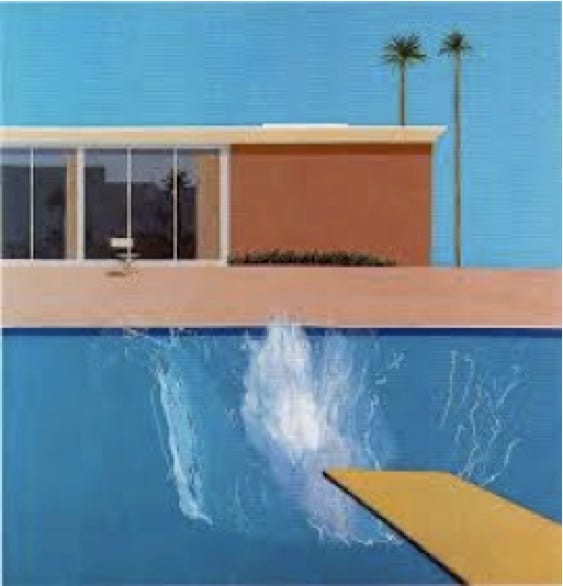

Artist David Hockney’s 1967 Southern California classic

“A Bigger Splash,” a painting emblematic of a specific moment in Los Angeles art history. In the mid-Sixties, David Hockney painted what is a more familiar kind of painting and subject matter for the artist. “A Bigger Splash” not only represented a definitive era in modern American art, but an iconic portrayal of luxurious living in Southern California. If art presumably imitates life, then the life that Hockney depicts is telling. There’s a clean, motionless and angular lines of a home with a deep blue pool and azure sky, void of human presence, but broken up by the splash that must have come from somewhere or someone.

Artist Ramiro Gomez' reinterpretation, entitled “No Splash” from his collection now on exhibit in Los Angeles called, “Domestic Scenes” Now a new Los Angeles artist has sought to provide an answer by taking a number of Hockney’s works and reinterpreting them with renditions of his own; just as Hockney did with Claude’s 17th C portrayal of the Sermon on the Mount. Turnabout is indeed fair play. Ramiro Gomez, Jr. does not simply answer the question, where are the people, but where’s the help? Where is the invisible presence of the underclass – the gardeners, the housekeepers, the pool man – who provides for others to enjoy such an opulent life style? And without whom there would be “No Splash.” Says one reviewer:

“Hockney portrayed white Americans in pristine, blue pools, with California’s modern architecture serving as the backdrop—the quintessential “American Dream.” In unmasking Hockney’s “American Dream,” Ramiro makes immigrants and domestic laborers visible, honoring their daily contributions and vital role in American society.”

Gomez calls his series of paintings, “Domestic Scene.” But he might more aptly have called it, “The Bigger Message.” It is this bigger message we’ll consider in the next commentary in this series.

© 2014 by John William Bennison, Rel.D. All rights reserved.

This article should only be used or reproduced with proper credit.

To read more commentaries by John Bennison from the perspective of a Christian progressive go to