Guest Essay: Is Jesus a Composite Character? The Evidence and Implications

by Harry T. Cook

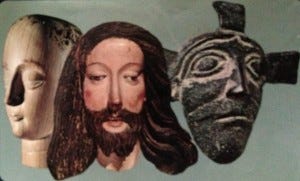

"The Faces of Jesus," with text by Frederick Buechner, left to right: 18th C Ivory Head of Christ, Mexico; medieval wood carving detail, Metropolitan Museum of Art, N.Y.; 11th C bronze relief, door of the San Zeno Cathedral, Verona.By Harry T. Cook

This month Words & Ways welcomed guest commentator, the late-Harry T. Cook. Harry’s info can be found at the end of this article, including a link to his last essay just days before his death in October, 2017. The following commentary was originally delivered at a recent Pathways Faith Community gathering. A pdf copy to read and/or print is here.

Is the Jesus of the New Testament a composite character? The question is a piece of research and textual analysis in which I have been engaged for several years. The question was born of years of dealing with gospel texts in the New Testament, as well as gospels not included in that familiar corpus. But why ask such a question? It probably wouldn’t be the first question that would be posed by one who has been conditioned culturally (and quite possibly catechetically) to assume that the name JESUS refers to the person so named in the pages of the New Testament gospels, as well as in the other 16 or so extant documents called “gospels.” Don’t underestimate the force of that conditioning. I will never forget my sister’s reaction when she figured out that the big department store we were taken to as kids to see Santa Claus actually had several Santa Clauses working at the ends of separate lines entering by separate doors so as to accommodate the large crowd of children waiting. She was aghast that Santa was not one person, which, of course, led her to the correct conclusion that Santa was a myth. My sister’s first shocked reaction is the very same as those who are offended by the mere articulation of the question: Is the Jesus of the New Testament a composite character? If, however, one came to the question as an entire stranger to the name JESUS and to the tradition built around that name, and if one spent some time with the textual material in which that name figures largely, he or she would have soon to acknowledge that there might well have been several different persons with the same name. Should he or she consult the works of Flavius Josephus, the proto-historian of the first century, it would be found out that in Josephus’ work alone are mentioned several Jesuses: Jesus son of Phabet, Jesus son of Anaus, Jesus son of Sapphias, Jesus brother of Onias, Jesus son of Gamaliel, Jesus son of Damneus, Jesus son of Gamala, Jesus son of Nun, Jesus son of Saphat, Jesus son of Thebuthus, Jesus son of Josedek, and a single entry (a few lines) in 814 pages set in 8-pt type about a Jesus, who, Josephus said, was a wise man, was the messiah and then goes on to paraphrase was Christians know as the “Apostles’ Creed.” The first thing this data tell us is that “JESUS” was a popular given name among Palestinians in the early 1st century of the Common Era. No wonder, because in the Aramaic of the time it was JOSHUA pronounced YESHUA, which means “one who saves.” So, in one sense, there was more than one Jesus in that time, probably many more. – Yet our unconditioned-to-general-assumptions friend would want to explore further. He or she would quite naturally turn to the western world’s all-time bestseller known as “the Bible,” and to its last 27 documents known as “the New Testament. I like to call it “the Christian appendices to the Hebrew Bible, which they are. In those pages of whatever you wish to call it are to be found much about a Jesus, THE Jesus about which Christianity has made such a big deal for so long. Josephus does not refer to that Jesus as the son of anyone – a curious omission. If our inquirer sought a little expert assistance, he or she would be directed to the earliest stuff in the New Testament to see what it has to say about any Jesus. That would be to Paul’s authentic epistles – those being in the order of their occurrence in the testament (not the chronological order of their writing, though): Romans, I/II Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, I/II Thessalonians and Philemon – none earlier than 50 CE, none later than 60. Yes, I have omitted Colossians and Ephesians because it has become clear to the multitude of scholars who have worked and are working on these texts that the vocabulary, style and subject matter of Colossians and Ephesians do not indicate that they are of the same voice as the earlier ones mentioned. Paul dictated his epistolary work to a scribe called in Greek a grammateus, whence our word “grammarian.” There are frequent mentions of a Jesus in those epistolary documents. None of them quote anything that Jesus elsewhere is credited with saying or doing -- save, possibly, the passage at I Corinthians 11:23-26 in which Paul says he is passing on “from the Lord” an account of what we call The Last Supper, quoting from Mark 14:22-25; with parallels at Matthew 26:26-29 and Luke 22:14-20. Supposing there was such a Jesus of whom Paul spoke, he tells nothing about him, save the Last Supper tradition Paul said he got from the Lord (“Lord” in most New Testament instances refers to the one some believed has be resurrected. That gives the passage a kind of supernatural or mythical tone). Most often Paul uses the term “Christ Jesus” (meaning essentially “The Anointed One – or Messiah – named Jesus”), and if one tracks Paul’s statements about this Christ Jesus -- Paul’s proclamations, really -- it becomes clear that Paul has turned some possibly historical personage from what John Dominic Crossan called “an itinerant sage” into a larger-than-life Graeco-Roman myth figure whose death and resurrection were the most important things about him – with no mention of the ethical wisdom other sources attribute to him. Our non-conditioned non-assumer would be quite justified in figuring, say, if the Jesus credited with the wisdom sayings that appear in what we call “the Sermon on the Mount” (in Matthew) or “the Sermon on the Plain” (in Luke) was or were different persons than the one about whom Paul spoke at length. – Now I know that what I just worked out there goes against the grain of everything many of may you think you know and may take for granted, which is the #1 problem scholars of these texts run up against, especially if such scholars happen to be parish priests, pastors or ministers. Whoever is studying the documents in question appropriately starts with what is best known among them: the four canonical gospels. Actually, to help me keep track of some of the relatively few things of which this kind of scholarship can be sure, I name them in the generally accepted order of their appearance in the first century: Mark, Matthew, Luke and John. How we have figured out that order is part of another lecture. Suffice it to say that the earliest of them appeared some time after 70 and 72 CE. Again, why we think that is another lecture. Now there are two things about that one dares not miss: One is that the “events” related as if by an eye witness in the earliest (Mark) to 40 years after they would have occurred. The supposed accounts are obviously based on oral tradition, which is only a step away from gossip. It’s akin to what a court of law calls “hear-say” and thus declines to admit it to the record. The second thing? Indications are that the Mark gospel was pulled together quite soon after, and (I have hypothesized) in response to the cataclysm of the thorough destruction of the Jerusalem temple, and, perforce, much of the tradition of Judaism to that point. My work on that hypothesis is, once again, fodder for another lecture another time. The Jesus of Mark’s gospel is a provocateur, even an iconoclast. He and his close friends are upbraided because they are not observing a required pattern of fasting. They are brushed off by Mark’s Jesus saying, “Can the wedding guests fast when the bridegroom is with them?” Those conditioned to the usual assumptions shrug their shoulders and say, “Well, after all he was the Messiah.” But the person new to all this might mutter, “What a conceited horse’s ass!” It is in Mark’s gospel we first encounter the iconoclasm concerning the Sabbath. The always-right righteous ones are offended that Jesus’s disciples pick off grain to eat on the Sabbath. That’s work. You can’t do work on the Sabbath. “Oh, yeah?” Jesus says. “The Sabbath was made for Adamh (or humankind), not humankind for the Sabbath. So Adamh is lord of the Sabbath.” That Jesus is one tough in-your-face, counter-cultural guy. And so it goes in Mark. And by the way, the Gospel of Mark was ended (we think deliberately) with a strange Greek locution: efobounto gar, which means “because they were afraid.” Who was depicted as being afraid were the women Mark said came to the cemetery to anoint Jesus’ body for burial. That was the author or editor of Mark perhaps being provocative, suggesting that his readers could decide whether or not Jesus was alive by what they ended up doing with their own lives. Try that out for an Easter homily or sermon, first locating on your GPS the nearest unemployment office. If Mark appeared in the early 70’s, Matthew is thought to have followed within a decade or so. It is clear to scholars that Matthew was based on Mark’s corpus, but the Jesus who shows up in Matthew was (rather than an iconoclast) an advocate of both the law and the prophets. His Jesus was always backed up in the text by some reference to what had been “said or predicted by the prophets.” -- Matthew’s Jesus was devoted to the law. Matthew went so far as to depict Jesus ascending a mountain to hand down a new Torah, that being the string of sayings the writer or editor of Matthew had collected from oral tradition and arranged them one after the other like the commandments of Torah. The translators and formatters of the English Bible in the 17th century dubbed ch. 5, 6, and 7 of Matthew “The Sermon on the Mount.” Also the Jesus we meet in Matthew is about divine anger, wailing and gnashing of teeth – the Holy Trinity of the fundamentalist’ hellfire-and-damnation show. There’s more to be said about the uniqueness of Matthew, but that will have to do for now. Luke takes a different approach. Luke’s Jesus is the storyteller par excellence. The grace-filled parables of the Good Samaritan and the Prodigal Son. John takes yet a different approach; very different. The Gospel of John frequently depicts a Jesus making his stand with “I AM” speeches. With hardly any of the ethical teaching found in Matthew and Luke, Jesus is a pronouncer. Out of the twenty or so gospels on might ask why those who formed the canon chose the documents they did. The church would tell you that the Holy Spirit dictated those choices, and you can believe that if you want; but you’d be short of data to back up that belief. The more likely scenario is that the 2nd and 3rd centuries of the evolving church – separated by many generations from any actual 1st century Jesus – had competing ideas about who he was, or they were – more likely though, who they wanted their own figure of Jesus to have been. Meanwhile, the four canonical gospels were the most credible among the lot. And that is a relative matter. I don’t see anything credible about Matthew 1:18-25 or Luke 1:26-38 – Joseph being told by a heavenly evangel that his girl friend is pregnant, but not to worry: the Holy Spirit was the one; Mary being told more directly that her pregnancy would be the result of the Holy Spirit – the text says – coming on or over her. Hmm. In the meantime, you can blame Matthew for getting the church into the virgin-birth business because whoever he was used the Septuagint’s Greek mistranslation of the Hebrew word “almah.” The Septuagint says Mary was a παρθενος, meaning sexually untouched, while “almah” merely means a woman of marriageable age. John Dominic Crossan, a major player among the masters of our trade, is convinced that the a Jesus was what he calls an “itinerant sage,” that is a wisdom teacher who went from village to village with his message. The contemporary version of such a person would be a newspaper commentator, or a radio or television pundit whose self-appointed task is to tell who ever will listen what the deal is and what should be done about it. In first century Palestine, with the exception of what technology of the period Rome brought, the peasantry was entirely dependent on the itinerant street speakers to bring entertainment, interesting viewpoints, religious teachings and political commentary. Much evidence exists that they were a familiar type. Crossan thinks that the Jesus he identifies as the real one was one of those types, or adopted that persona and its strategies in order to get heard. My 2003 book SEVEN SAYINGS OF JESUS explores that idea and suggest that those sayings or examples of ethical wisdom fit Crossan’s type. [Those sayings being: Turn the other cheek, walk the second mile, give up your shirt as well as your coat, love your neighbor, love your enemy, forgive as often as it takes and treat others as you yourself would be treated.] These wisdom sayings appear in the both Matthew and Luke, one of them also in the Gospel of Mark – and all are considered to have had their origins in a document called “Q” – from the German “Quelle” or “source” – in other words a collection of sayings attributed to a Jesus that came along as oral tradition, maybe also written, prior to Mark and the others. The sayings, if they originated with a Jesus reveal a gentle radical -- a kind of Mohandas Gandhi rather than the overt iconoclast whom we see in Mark. – Now there is another document called a “gospel” – the Gospel of Thomas about which there is an interesting story, which I shall tell now, but what I want soon to do is to contrast the gentle radical of the “Q” sayings with the rougher and somewhat uncompromising sayings in Thomas. The existence of the Gospel of Thomas was inferred from allusions toand quotation of some of its passages in3rd and 4th century documents, but it itself was lost to the ages until in 1945 near the upper Egyptian settlement of Nag Hammadi which sits on the west bank of the Nile. The story is that a Bedouin ducked into a cave to stay out of a rare rainstorm, and when his eyes became accustomed to the light, he spotted several jars in which were codices of what appeared to be very old. They were. The short story is that they consisted of a number of writings, most interesting of which was the long-lost Gospel of Thomas. The Nag Hammadi text was in Coptic, but certainly translated from a much earlier version. Archaeologists have thought that the codices were hidden in the cave and that they had been in the library of a nearby monastery whose monks had to get them out because possession of them at the time was considered to be heresy – a crime. Princeton scholar Elaine Pagels makes it clear that she thinks Thomas was very nearly contemporary with Mark. Some of us think it is as early as 50 CE, and contemporary with Paul’s epistolary output. In her 2003 book BEYOND BELIEF: THE SECRET GOSPEL OF THOMAS, Pagels makes a case that the Gospel of John was written in part to present a Jesus very different from Thomas’ – a Jesus who was God in the flesh, rather than the cranky dyspeptic revealed in some of the difficult sayings in Thomas. She points to the passages late in the Gospel of John that have to do with a guy named – guess what? – Thomas the doubting one. A few post-resurrection mysterious appearances, and you have a divine savior and a discredited Thomas. And that might be why the monastery near Nag Hamadi had to get the Thomas codices out of the library as the gospel named for the doubter had been declared heresy. Ultimately, the church chose the Jesus of John over the Jesus of Thomas. Here are some of the sayings credited in the Thomas gospel to Jesus: Blessed are the solitary and elect, for they will find the Kingdom and Whoever has come to understand that the world has found only a corpse . . . is superior to the world. Two reasons, as you can plainly see, why Thomas was not taken into the canon. Note these other sayings: 53, 60, 104, 107. Thomas’ chief error, the hierarchy would conclude, was that his Jesus was a humanist who believed that whatever was worth anything was in a person, among a community – not somewhere up there or out there, and nothing needing mediation of a priesthood. This is what Pagels writes:

According to Thomas, Jesus rebuked those who sought access to God elsewhere, even – perhaps especially – those who sought it be trying to “follow Jesus” himself. When certain disciples are depicted as pleading with Jesus to “show us the place where you are, since it is necessary for us to seek,” Jesus does not bother to answer so misguided a question, and redirects the disciples away from themselves toward the light hidden with in each person.

When I first read that passage in Pagels’ book, immediately what came to my mind was a poem (later set to music) composed by my late friend, the pioneering humanist rabbi Sherwin T. Wine: Where is my light … truth … hope?. . in me and in you and in you. Such theology was anathema to the growing cult of Christianity in the 2nd and subsequent centuries. It needed a God-man, not a fusty rabbi as its leader. So Thomas and his Jesus were suppressed. Thomas’ Jesus totally contradicted Mark’s Jesus on the matters of fasting and the Sabbath. The Thomas saying goes: If you do not fast as regards the world, you will not find the Kingdom. If you do not observe the Sabbath as the Sabbath, you will not see the Father. So what we have are parts, some fragmentary, of documents called “gospels” with their central characters being called “Jesus.” The default position of many Christians is that it must be a case of people seeing the same thing or the same person from different angles and through different lenses, and that there was but one Jesus and there could not be another; and that he was and is the son of the only god. But while not conclusive, the evidence points in the other direction. It suggests that the Jesus of traditional Christianity may be more an idea than an historical person who lived between 4 BCE and 30-some CE.

While not conclusive, the evidence points in the other direction. It suggests that the Jesus of traditional Christianity may be more an idea than an historical person who lived between 4 BCE and 30-some CE.

There are only indirect allusions to the traditional figure of Jesus outside of the Bible and writings traceable to early Christians. Tacitus Book 15 of his “Annals” mentions one “Chrestus” who was condemned to death under the reign of Tiberius (14-37 CE). Suetonius in his “Life of Nero” refers to Christians as “a class of men given to a new and wicked superstition.” That’s about it. All that said, it is very difficult in a rational world to posit the Christ of faith as opposed to the Jesus of history, because the “Jesus of history” is, as we have seen (if we wanted to see), an illusive figure about whom there is not much agreement among textual sources. Yes, of course, the church has its doctrines and tenets of faith, but were the church to deal honestly with the textual research and analysis that has been underway for most of 200 years, it would change a lot. The thing is that such institutions as the church – especially the historic communions – would not have much of a foot to stand on if it admitted to the inconclusive but persuasive evidence that there may have been more than one Jesus in Christianity’ past. Which one did not invite women to be disciples? Which one died on a cross? After all, thousands of people were crucified during Jewish-Roman wars. Which one was the object of eerie stories about a resurrection? Which one performed alleged healing miracles? Which one went from town to town with his ethical wisdom teachings? Which one was the dying and rising son of a god among hundreds of such mythological figures variously worshipped during the first century CE Graeco-Roman world? The evidence is what it is, and is still being sorted through, by people like me; not because we want to debunk traditional faith, but because we are researchers who go where the data lead. I did not start out fifty years ago in graduate school to become the pain in the neck I have became to ecclesiastical authorities and others who wished to be neither disabused of their beliefs, nor shown the impossibilities of some of them. So the implications of the research I have been describing as the as-yet-unripe fruits of which I have been sharing with you range from “So what?” to “Panic” in the rectories, manses, episcopal palaces and wherever people read books, no matter how controversial their content. With such stars in our field as Crossan, Paula Fredriksen and Elaine Pagels appearing from time to time on PBS discussing their findings, much of which we have talked about is startling enough that people wonder. People who wonder are people who ask questions. People who are forward enough to ask questions expect clear answers. They expect to be told what is known about the issues in which they are interested. They expect to hear their clergy leaders tell the truth about such matters as, well, Jesus. The implications of being honest from the ambo or the pulpit are to some who talk from them downright frightening. Church types do not like to give up what authority and control they may have by virtue of their titles they may have accrued over longevity. When one can no longer say, “Do this” or “Do not do this” because Jesus hates it, there is definitely a loss. But the author of the Gospel of John, whose Jesus was adopted whole cloth by the church, let something slip there in the eighth chapter at the 32nd verse. He puts these words on his Jesus’ lips: “And you shall know the truth, and the truth will set you free.” John probably didn’t mean the kind of truth scholars of the Bible are pursuing in archaeology and textual analysis. He probably meant the “truth” that would be uttered by himself and others presuming to speak for God. Yet he would have known (one presumes) that the Greek word he used -- αληθεια – means “unveiling.” Notwithstanding, knowing that something is true, or that something is not – that is, has or has not been shown to be the truth -- is more than freedom. It is power. Like knowledge, it is power. Letting loose such a set of data as we have explored here – as inconclusive as yet they are – has enormous implications for believers; especially eager, true and committed believers. The upside of it all is that people who yearn to think for themselves will have plenty to think about for a long time to come for they will have entered a world in which contingency is for real, in which you have to present the results of actual research and reason to be taken seriously; in a world in which people realize that truth is not found, but made – made in the communal act of learn-edconversation as contradictions of formerly accepted truisms are acknowledged. Someone once asked me what would become of the church if enough people decided that Jesus was a composite character. My answer was, the church with the proper leadership would discover that it isn’t doctrine or creeds or other false certainties that make the church, but community; communities of human beings who care about one another, who take wisdom where they find it, inspiration to do good and be good wherever and however they stumble over it. Certainly the ethical wisdom attributed to a Jesus by Thomas or Matthew or Luke or sometimes Mark can’t steer you wrong. Loving enemies tend to make them neighbors; with whom loving is the other half of that piece of wisdom. Turning the other cheek sometimes stays the cruel hand. Walking the second mile voluntarily has the advantage of disarming the guy who used his petty little power to make you do the first. Treating others as you wish to be treated has its obvious value of making peace. So the implications of the question of multiple Jesus-es having been folded into an essentially fictitious composite character are really what anyone or any community will make of them. I’d like to live long enough to see somebody other than the Unitarians get to that point.

Harry T. Cook Harry T. Cook was a retired Episcopal priest whose primary area of research included first century CE biblical texts and Christian origins. He was a graduate of Albion College and Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary at Northwestern University with honors in Hebrew. He was the author of Christianity Beyond Creeds (1997), Sermons of a Devoted Heretic (1999), Seven Sayings of Jesus (2003), Findings: Lectionary Research & Analysis (2003) and Asking: Inquirers in Conversation (2010), Resonance: Biblical Texts Speaking to 21st Century Inquirers (2011), Long Live Salvation by Works: A Humanist Manifesto (2012) and What a FriendThey Had In Jesus: The Theological Visions of 19th and 20th Century Hymn Writers (2013). For many years, he wrote an insightful weekly commentaries on the appointed texts of the Common Lectionary, along with a weekly essay on current hot-button topics. His website was: www.harrytcook.com Harry's last commentary shortly before his death in October, 2017 is here.